SCAMWATCH

- Oct 1, 2020

- 5 min read

MADI SCOTT|NEWS

“Would you like to work from home and become a millionaire?”

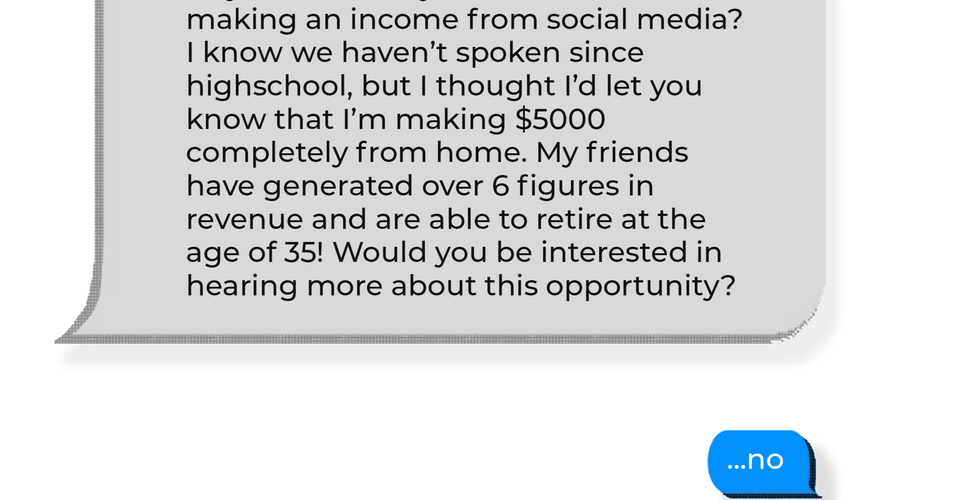

There is always that brief moment after someone you barely know reaches out through Instagram with an amazing #bossbabe work opportunity and it makes you wonder, could it work? The temptation is real, with success stories flooding social media of globe-trotting insta-savy women making cash quickly and easily, and the best part is that for just a small start-up fee, that can be your life too. But as they always say, if it’s too good to be true, it probably is.

Pyramid schemes and Multi-Level Marketing companies have been a staple part of Australian suburban life for decades, with the door knocking Avon ladies of the 1960s now taking on the form of sleek websites and social media campaigns, promising the perfect work-life balance for Australian women. These get-rich-quick schemes appeal to everyone, and through psychological marketing have reached an estimated 576 000 people this year alone, accumulating to $1.38 billion in sales annually. But, for such a successful marketing scheme an estimated 99.4% of recruits lose money.

So how do they work?

There’s a big difference between Pyramid schemes and Multi-level Marketing (MLMs), with pyramid schemes now illegal in most countries including Australia. Pyramid Schemes survive on recruitment, charging new members a start-up fee to join. Once you’re signed up, it is then expected for you to recruit others, starting an endless cycle of promoters at the top of the pyramid making money on new recruits. Big up-front costs and high collapse rates leave a majority of members out of pocket with nothing to show, with horror stories often outweighing the select few successful ones. Often pyramid schemes will use overpriced, poor-quality products to disguise their true purposes, however this is almost always a way to hide their main objective of recruitment.

Whilst Pyramid Schemes make money through recruitment, Multi-Level Marketing is a strategy used by direct stake companies who encourage distributors to recruit new distributors and pay a percentage of their recruits’ sales. This legal system allows representatives to earn a commission on the products they sell and for every new recruitment you employ. Whilst there are fundamental differences between pyramid schemes and MLM’s, it is often hard to distinguish the two, with many pyramid schemes hiding behind the legality of the title ‘MLMs’.

Whist statistic after statistic proves the majority of people in these sales structures don’t make money, often revealing financial losses instead, why do people still join? Companies such as Tupperware, Younique, and Young Living are still seen by many Aussies as a legitimate and worthwhile way to try and make some extra cash.

But how much money can you actually make?

Take an MLM like Tupperware, a company that’s long been a favourite with Australian mums. Started in 1946 in the USA, Tupperware and its unique marketing method of Tupperware parties has become a staple in Australia since the early 60s. The multi-level marketing strategy adopted by Tupperware has often been criticised, yet the company argues their consultants are well-rewarded. During their August promotion, the company advertised that after buying the ‘start me now business kit’ for $199 and successfully completing the onboarding programme, consultants can earn 20% on everything they sell. Whilst it is portrayed as an easy work-from-home opportunity, figures from2018 of the American branch reveal 94 % of Tupperware’s consultants remain on the bottom tier, with an average profit of only $653 a year.

Whilst it is definitely possible to make a profit, albeit likely a small one, there is a lot at stake, with a rising disdain for people working for MLMs. The Australian Facebook Group “Sounds like MLM but ok” boasts over 180 thousand followers. With such an emphasis on recruitment, employees of these pyramid-like structures usually have to reach out to friends and family to grow their network. Although it does not sound that bad, inviting a few friends or family members to these product parties, social media parodies found on Tik Tok and heartfelt stories on Facebook reveal the awkward and common dissolvent of friendship thanks to the pushy and financially dependent marketing strategies.

It is not just the strain on relationships that tarnishes the image of MLMs, with a surprisingly dark history surrounding many of the largest companies. For a marketing strategy that strongly depends on the brand image looking legitimate and as real as possible, numerous MLMs have been investigated for unlawful conduct and many others attempt to hide some not so squeaky-clean beginnings.

Young Living, a popular essential oil company reliant on MLM strategies to expand their reach worldwide was founded in 1993 by Donald Gary Young. Whilst today their products are advertised as the best, most authentic essential oils in the world, promising life-changing benefits, the company’s history is marred by tragedy and some very questionable claims. Young Living's Australian website currently makes no mention of Donald Gary Young’s past charges of practicing medicine without a license, and the numerous lawsuits and convictions tied to the owner’s Young Life Research clinic, which was opened in 2000. There have also been multiple claims made by Young Living, marketing their essential oils as treatments for medical conditions and viruses. In 2014, the company was also warned against marketing their products as a prevention method from Ebola.

Even with a tumultuous past, Young Living is one of the largest MLMs today, with over 3 million members worldwide. Becoming a member not only gets you 24% off retail pricing, but also commissions and invitations to exclusive events. The compensation plan outlines the pyramid-like structure of the company, outlining the levels of members, stars, senior stars and executives.

Despite the company boasting the chance to earn a bonus of over $2990 by achieving all four levels, a class action filed in December 2019 in California argues it is nearly impossible to make that amount of money. Young Living's 2019 worldwide income disclosure reveals the average income for all members was $236, despite the fact that 89.6% of distributors were on the lowest tier with an average income of $3. The complaint further argues that the system is designed for a sole purpose: to recruit new members and to grow the illegal pyramid, which only benefits those at the top.

But even after lawsuits and class actions, numerous cautionary tales and the toll on friendships, why are so many Australians signing up?

An estimated 75% of MLM members are women and whilst this can be largely attributed to the stay-at-home nature of the work, it also highlights a growing problem in Australia; the financial literacy gap of women. Whilst women in Australia aged between 25 and 40 are the fastest growing wealth demographic, money is still the number one cause of stress. So the next time you’re invited over to the neighbours out of the blue or get a ‘dm’ from a not-so-close acquaintance, remember it is too good to be true.

This article was originally published in the 2020 issue, BREAD.

Comments