Smithsonian Scrubs Queer Context From Famous AIDS Artwork

- kayleighgreig

- Jul 23, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Sep 13, 2025

Editorial Assistant Helio Russell reports on the erasure of queer context from significant queer artworks in the Smithsonian.

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery has been accused of erasing the queer context of the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres, an artist famously associated with the AIDS crisis of the eighties and nineties. The current criticism revolves around his 1991 piece, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), whose current wall text provides no queer context.

The outcry follows the debut of Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return, an exhibition currently running at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. The exhibition was co-curated by the Archives of American Art’s Josh T. Franko and the National Portrait Gallery’s own Charlotte Ickes, and purports to explore Gonzalez-Torres’ “deep engagement with portraiture and the construction of identity, as well as how history is told and inherited.” [1]

Art critic Ignatio Darnaude wrote an opinion piece for OUT Magazine in January 2025 decrying the exhibition’s treatment of Gonzalez-Torres’ work. Darnaude alleges the National Portrait Gallery’s decisions regarding Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), including omitting the biographical information or traditional interpretation behind the piece, “destroys the monumental allegorical and emotional impact” of the portrait. [1] His disappointment extends to the exhibition’s introduction, which also neglects to mention the socio-political or personal context of the artist's work, as well as the decision to display the candy-pile in a neat path across the floor, rather than piled against a wall, as it is traditionally shown. [2]

Darnaude is not the first to raise this concern. In a 2017 article for POZ magazine, art critic Darren Jones expressed a similar sentiment about an exhibition of Gonzalez-Torres’ work at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York. Jones was critical of the exhibition text for Portrait of Ross, as well as Untitled (A Portrait), a piece consisting of a series of white-text phrases appearing on a black screen, including, among others, “a white blood cell count”, “a new lesion”, and “a hateful politician”. The gallery’s exhibition text claimed the subject was “unspecified” and that viewers were encouraged to “provide their own imagery and associations.” [3]

Both Darnaude and Jones attribute the shift in curatorial practice to the David Zwirner and Andrea Rosen galleries, who co-represent Gonzalez-Torres’ estate as of 2017. They point to the Smithsonian’s 2010 exhibition Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture, which directly linked Ross’ portrait to the AIDS crisis. The theory goes that galleries seek to minimise Gonzalez-Torres’ association with the AIDS crisis in order to appeal to the upper echelon of art buyers, who historically favour heterosexual, white, male artists. Darnaude links the decision to today’s political climate of homophobic backlash, characterised by queer book-bannings and anti-LGTBQ+ bills.

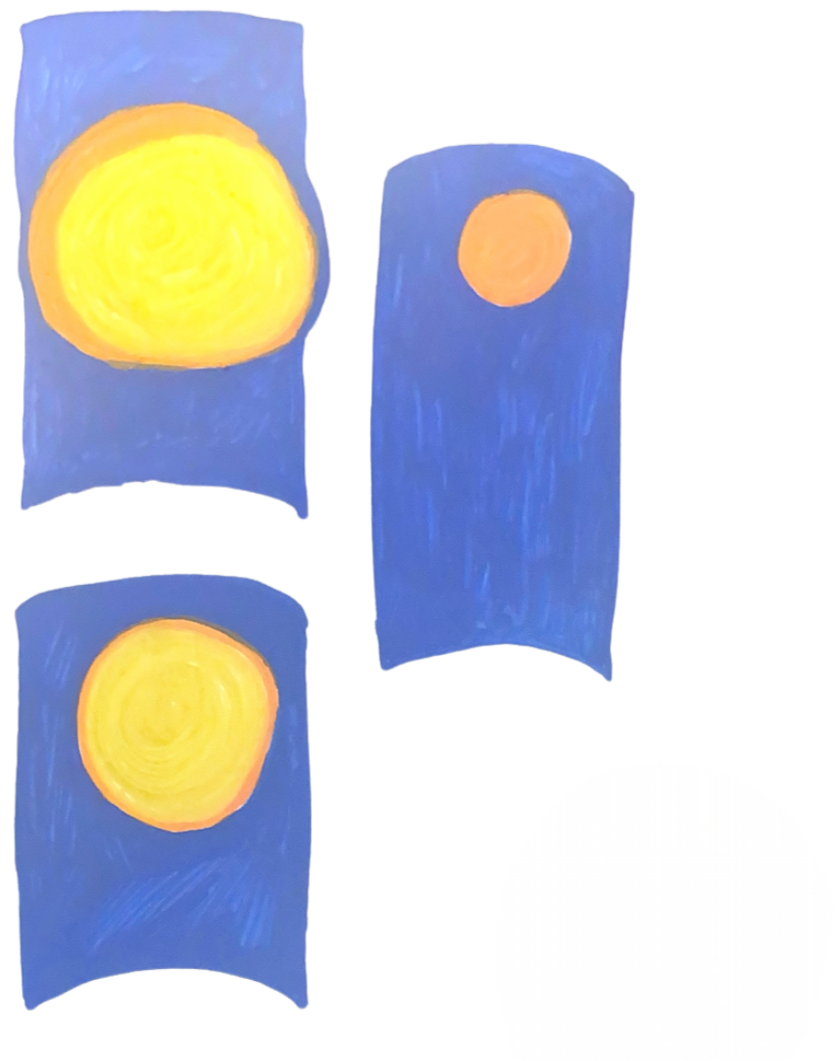

Portrait of Ross, first exhibited in 1991, consists of 175-pounds of brightly-coloured wrapped candy, traditionally in a pile leaning against a wall. Onlookers are encouraged to take a piece and eat it, and watch the pile diminish as a result of their actions. The museum or gallery is to replenish the pile at regular intervals to reach the 175-pound standard. [4]

The portrait, which represents its subject through their weight and density rather than image, has been traditionally interpreted to represent Ross Laycock’s physical deterioration and eventual death at the hands of HIV/AIDS. By taking a piece from the pile, onlookers participate in this degradation, leading them to consider their culpability. Themes of public responsibility bring to mind the US government’s fatal inaction regarding the AIDS epidemic. However, by replenishing the portrait, the museum or gallery turns back the clock on this symbolic death, thus allowing Ross, or at least his representation, to live forever.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres was born in Cuba in 1957, and moved to New York in 1979 to pursue an education in Fine Arts. He became known for his minimalist style and the conceptual strength of his installations, typically made from everyday objects. He met Ross Laycock in 1983, who would become his life partner and muse until his eventual HIV/AIDS diagnosis in 1987 and death via AIDS-related complications in 1991. Gonzalez-Torres passed the same way in 1996. [5] Of his work, he said “it’s very political. Because you are going against the grain of what you are supposed to be doing. You are not supposed to be in love with another man, to have sex with another man … great work has sentimentality and ruthlessness in the perfect balance.” [6]

The National Portrait Gallery has defended itself on Instagram, citing references to Gonzalez-Torres’ and Laycock’s life, as well as a focus on queerness, throughout the exhibition. The gallery’s account posted a picture of the wall text for an 1891 photograph of poet Walt Whitman by Thomas Eakins, exhibited in the same room as Portrait of Ross in order to posit the nineteenth-century poet as a “queer ancestor” of Gonzalez-Torres. The exhibition text for Eakin’s photograph mentions Ross Laycock and his death via HIV/AIDS in conjunction with Portrait of Ross, although the exhibition text for the latter work does not. [7]

The Gallery and its defenders have argued that Gonzalez, as a postmodern, minimalist artist, favoured open-ended interpretations of his art. The artist named each of his works “Untitled” then provided a subtitle, an artistic habit shared by artists like Donald Judd and interpreted towards this end. [8] Likewise, in a 1995 interview, he said “I want some distance. We need some space to think and digest what we see. And we also have to trust the viewer and trust the power of the object.” [9]

Individuals who were close to the artist, such as artist Carl George and museum Director Bill Arning, have joined critics in decrying the gallery’s treatment of the artwork. “Bullshit”, George writes. [10] Arning says, “[Gonzalez-Torres] was very specific about the works being informed by watching Ross fade away, lose weight, and disappear from his life, and I am pretty sure he would be more pissed off by the omission of the mention of the specifics of Ross’ death—that was his biggest sorrow—than his own”. [11]

The comment sections of both Darnaude’s and the Gallery’s posts are packed with people weighing in on the discussion. Instagram user parma.ham’s criticism of Portrait of Ross’s wall text revolves around it being “not that accessible. I also think it’s worth noting that people under the age of 25 know little about the HIV crisis,” they explain, “let alone understand the experience of it.” [12] Another user, davidglenndixon, argues that the title is context enough, “you should be able to get it from that… The fact that some people will consume Ross’s body thoughtlessly while others will do so sacramentally is not incidental to the piece. It is the piece. There is slyness as well as sorrow in knowing the ignorant will probably stay that way.” [13]

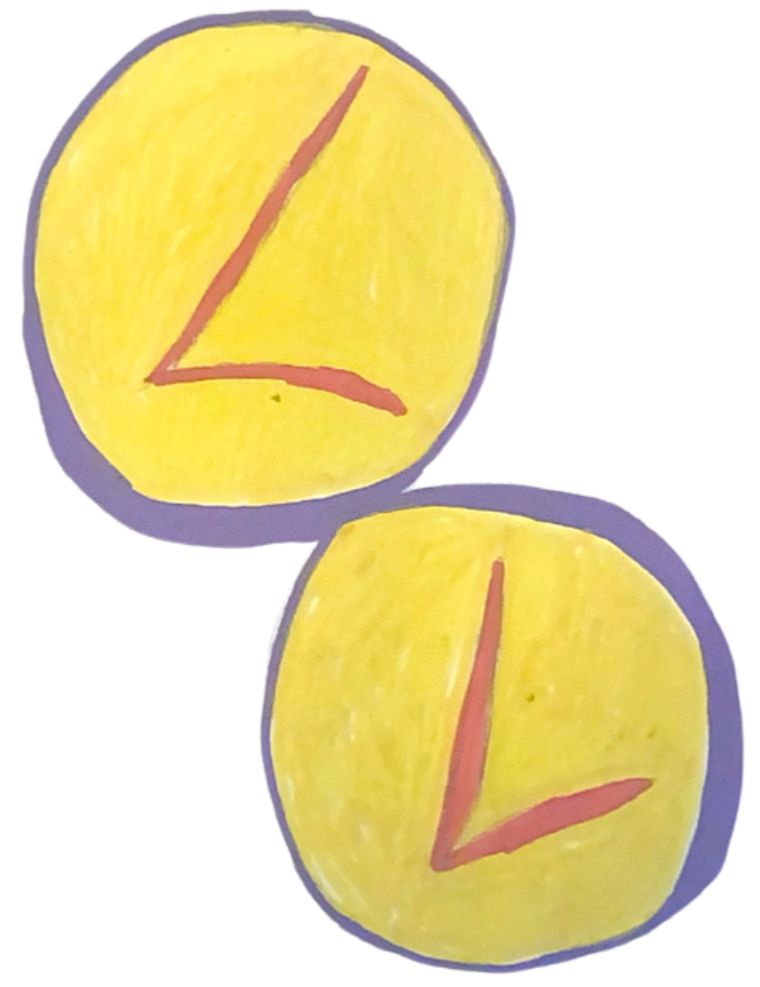

Felix Gonzalez-Torres once cited Laycock as the primary audience for his work. When alive, he was explicit about his goal to immortalise Laycock through works such as Untitled (Perfect Lovers), two clocks side-by-side in perfect synchronicity. The clocks tick as one until inevitably, the battery in one or both begin to run down. The lovers’ rhythms grow further apart, and eventually each stops, silent reminders of a once perfect harmony. [14]

On witnessing Laycock’s death, Felix said: “when he was becoming less of a person I loved him more. Every lesion he got I loved him more. Until the last second.”... “I never stopped loving Ross. Just because he’s dead doesn’t mean I stopped loving him.” [15]

ENDNOTES:

[1] “Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Always to Return.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian, 17 Jan. 2024, npg.si.edu/exhibition/felix-gonzalez-torres-always-return.

[2] Darnaude, Ignatio. “The Smithsonian’s queer erasure of an AIDS artwork should alarm us all.” OUT magazine. 24 Jan. 2025.

[3] Jones, Darren. “Galleries representing Felix Gonzalez-Torres Are Editing HIV/AIDS From His Legacy: It Needs to Stop.” POZ Magazine. 8 June, 2017.

[4] “”Untitled”: Portrait of Ross in L.A.” The Art Institute of Chicago. N.d.

[5] Graf, Stefanie. "Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Haunting Works of an Artist Afflicted with AIDS" TheCollector.com, May 30, 2021.

[6] Bleckner, Ross, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. “Felix Gonzalez-Torres.” BOMB, no. 51, 1995, pp. 42–47. JSTOR.

[7] Smithsoniannpg. “Let’s take a closer look at an artwork by Felix Gonzalez-Torres”. Instagram. 1 February 2025.

[8] Pugh, Nathan. “From Candy to Lightbulbs, Felix Gonzalez-Torres Showed Life and Loss Through Everyday Objects”. Smithsonian, 21 October 2025.

[9] Bleckner, Ross, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. “Felix Gonzalez-Torres.” BOMB, no. 51, 1995, pp. 42–47. JSTOR.

[10] Greenberger, Alex. “Felix Gonzalez-Torres Show in DC Spurs Accusations of ‘Queer Erasure’ in Smithsonian Show.” ART News, 29 January 2025.

[11] Jones, Darren. “Galleries representing Felix Gonzalez-Torres Are Editing HIV/AIDS From His Legacy: It Needs to Stop.” POZ Magazine. 8 June, 2017.

[12] Parma.ham. “I also think it’s worth noting that…” Instagram. February 2025.

[13] Davidglenndixon. “Back when I worked for a different Smithsonian Museum…” Instagram. February 2025.

[14] Graf, Stefanie. "Felix Gonzalez-Torres: Haunting Works of an Artist Afflicted with AIDS" TheCollector.com, May 30, 2021, https://www.thecollector.com/felix-gonzalez-torres-haunting-works-aids-artist/

[15] Bleckner, Ross, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. “Felix Gonzalez-Torres.” BOMB, no. 51, 1995, pp. 42–47. JSTOR.

Comments